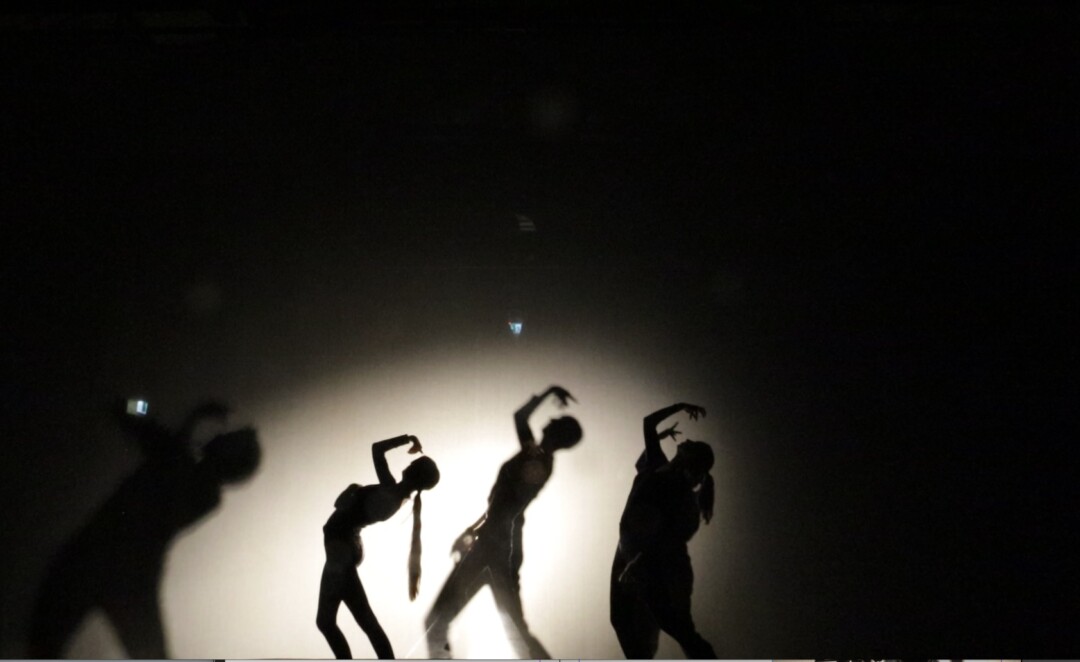

Our 2023 Research Fellow Helen[e] Markstein has put together a unique library of Parkinson’s movement vocabulary. This invaluable resource “widens choreographic potential by bringing Parkinson’s movement to the dance and wider community, demonstrating that disability movements are no barrier to creative movement work.”

As Helen[e] puts it, we are “firstly creative secondly disabled”:

“The human body is so capable. To constantly be able to invent different ways of creative movement. To be told one is disabled means being told you are unable. Unable to do, to reach what able humans can. I would like to show that whatever the endeavour, creatively it can be attempted, supplying new and inspiring outcomes and furthering the acceptance of change for creatives who are firstly creative and secondly disabled. I hope to show other sufferers of this disease, that there can be interesting creative opportunity in the disorder itself, by working with what you’ve got.”

Helen[e] has used design principles from her practice as a scenographer to bring order in what is considered chaotic. She firstly digitally captured the many movements that exist in her Parkinson’s affected body (those involuntary and the corresponding voluntary reactions, such as concealment); then categorised and named them to finally offer them as a distinctive choreographic language to her dancer-choreographer collaborators. This movement library of PD gestures was used in the studio as “a starting point for choreographic investigation” and now remains an ongoing resource for the making of contemporary dance. By bringing Parkinson’s movement to the dance it “helps dance practitioners raise physical awareness” and expand their choreographic potential.

One of Helen[e]’s research questions was: Is it possible to make interesting choreography from involuntary disease movements?

“All my interest in movement life I have been in search of authentic body movement as a way to write original choreographic scores. With the PD diagnosis I have travelled from embarrassment, concealment, with the fear of no cure, never being able to make performance again, to a cautious observation, that developed into an about-face, for an unblinking (another symptom!) look at the creative opportunity this particular movement gives and how it could be used as a vocabulary to find/write/make performance.”

Working with and maintaining tremor was challenging for the dancers, which was something to embrace and transform into a creative opportunity:

“In the studio often it was observed and commented on how exhausting it was to maintain the tremor. We did quite a bit of work on this ‘Pausing’. It seems to go against a dancer’s grain, all this stopping, pausing and being bound. None of the dancers liked working with the bindings. At one point I was close to abandoning the restraints, worrying that it was all too much. But last minute looking at it, I thought it is so upsetting for the dancers, there must be something there to look at.”

You can access TREMOR: Movement Vocabulary HERE

And see some of the choreographic responses in the video below:

The video features dancer\choreographers: Anca Frankenhaeuser, Fiona James, Natalie Wadick, Natasha Padula. Guests: Patrick Harding-Irmer and Susan Weule.

FEATURED IMAGE CREDIT: Still from video, by William Bullock